Written by Declan Murphy.

Edited by Rayna Almas.

Designed by Tvisha Lakhani.

Published by Maryam Khan.

Popular pollinators like hummingbirds, bees and butterflies are nearly universally beloved. Today, let’s talk about some less well-known and much less popular pollinators in our gardens and fields, including at least one that is almost universally hated.

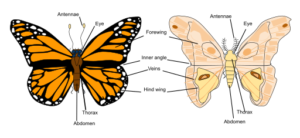

In the same family as butterflies, Lepidoptera, moths are generally considered less pretty and popular than their butterfly cousins. While moths are not the most hated insects around, they still get a bad rap for being annoying around porch lights on warm summer evenings. Nonetheless, we still owe moths a debt of gratitude for their important role in pollination. Approximately 80% of all flowering plants rely on pollinators to propagate, and moths play an often role in this process. While butterflies take the day shift, moths are out there working the night shift, and multiple native plant species depend on moths for pollination. Yet, their population is in decline, largely due to habitat loss, insecticide or trap use, and light pollution – those same porch lights they frequent at night are killing them in high numbers.

Like the moth, wasps have a much more popular relative in the bees, but also fairly important pollinators. Wasps are much less welcome in most gardens, however, because they have a reputation for being aggressive, with an unpleasant sting. However, wasps are also pollinators! Bees actively collect pollen to feed to their young, which generally makes them more efficient at the task, while wasps only pick up pollen while seeking nectar. Nevertheless, even accidental pollination is important to our ecosystems.

In your kitchen, ants can be a big nuisance, but in your garden, ants should be seen as welcome friends. Not only do they clean up debris, occasionally snack on harmful insects, and guard their favourite plants from parasites, but ants also serve as unrecognized pollinators for a few plant species. While not as effective as their winged colleagues, more than 70 different ant species take an active role in pollination worldwide.

While insects take center stage in how most of us imagine pollination, there are many non-insect pollinators in the world, as well. Lizards, for example, as well as some types of possums are also pollinators. Some of the much less popular non-insectoid garden residents, though, almost never get credit for pollination compared to how much they are disliked – rodents.

Pollination by small non-flying mammals (particularly rodents, marsupials and tiny primates) is known as therophily, and some plant species in the world have actively adapted to this form of propagation, especially in the tropics and in rainforests. Rats and mice, though not beloved, often transfer a good deal of pollen as they scurry through gardens or wooded areas, or as they search plants for nectar or seeds.

Importantly, many rodents are also responsible for the spread of seeds in wild areas, especially of trees and fruits.

Flying mammals have also gotten in on the act of pollination, as well. The focal point of many a nightmare, bats are, nonetheless, incredibly important animals in our ecosystems. Not only do bats keep insect populations down, but they are also key pollinators, with over 500 plant species relying on them for reproduction! Many plants that flower nocturnally depend on bats; some have even evolved big, bright white or pale flowers that may not appeal so much to birds or bees but glow in the dark just right to attract bats.

The agave plant, an important crop in Mexico, used to require bats to survive. However, since agave farmers often harvest the plant before flowering, most plants have to rely on cloning, now. As a result, the genetic diversity of the commercial agave plant has steadily declined, and so has the lesser long-nosed bat that evolved to both pollinate them and live off their fruit.

Saving the worst for last: Probably the most hated insect during Ontario summers is the bloodthirsty mosquito, with a massive industry dedicated to ways to eradicate the insect. Aside from its ability to carry disease, the mosquito can cause discomfort and ruin many a bonfire sing-along. Yet, while it is most well known for its collection of human blood, only the female mosquito bites, and only to nourish its eggs. Surprisingly, adult mosquitoes feed themselves nectar from plants, and wherever you see nectar-feeding, you also find pollination! While most plants can benefit from mosquito visits, some orchid species rely primarily on mosquitoes for their pollination services.

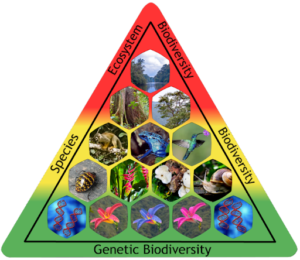

Moths, wasps, ants, rodents, bats and mosquitoes – very few people love the presence of these creatures in their gardens, yet nature makes use of even the unpopular, reminding us that human enjoyment is not the judge of a species’ worth. Further, in the attempt to rid our gardens and parks of unpleasant species, we certainly run the risk of destroying some unrecognized pollinators, as well as harming the more popular ones accidentally and damaging the delicate web of biodiversity that supports all life on earth.

Pesticides and insecticides often present a threat far beyond the species they are designed to kill, and we need to recognize that human intervention often has grim consequences beyond their main intent. Humans must embrace control measures like observation and prevention, rather than relying on more destructive means to reduce pests.

Given the danger of West Nile Virus (carried by mosquitoes) and other issues arising from some of these unpopular pollinators, humans are not unreasonable to want to control their populations in and around their homes, or in populated areas. An overabundance of rodents, for example, can spread illness and present a threat to human and pet safety. Nevertheless, protecting our biodiversity is crucial, even when it’s annoying. To reduce mosquito populations, dumping all standing water to avoid creating a breeding ground and encouraging the presence of their natural predators (such as bats) is a much better way to control their numbers than resorting to toxic means. The loss of one link in the chain of biodiversity can cause a rippling effect with significant consequences, and we have to pause to count the cost of such measures.

What’s your favourite pollinator? What’s your least favourite? Feel free to let us know in the comments!

Sources

Anon. (2018.) Rodents as Pollinators

Anon. (n.d.) Bats as pollinators – Why bats matter – Bat Conservation Trust

Daily, L. (2022.) How to get rid of mosquitoes without killing friendly pollinators – The Washington Post

Das, S. and A. Das. (2023.) Ants are more than just curious bystanders to some flowers—they act as significant pollinators

Fährtenleser. (2019.) File:Biodiversity Pyramid (English).png – Wikimedia Commons

Froschauer, A. (2012.) Image: Brown Bat.

Garland, S. (2019.) Mosquitoes – important pollinators?

Hooks, C.R. & A. Espindola. (2021.) Rodents and Other Non-Flying Mammal Pollinators – Maryland Agronomy News

Hundt, L. (2012.) Bat Conservation Trust: Variety is the Spice of Life

Kutcher, S. (2013.) File:Mosquitoes (10703811283).jpg – Wikimedia Commons

Mizejewski, D. (2020.) What Purpose do Mosquitoes Serve?

Mrice20. (2019.) File:Butterfly vs moth anatomy.svg – Wikimedia Commons

OSU. (n.d.) Wasps are pollinators too | OSU Extension Service

Parletta, N. (2020.) Step aside bees, the ants are pollinating

PennState. (2023.) Moths-The Forgotten Pollinators — Monroe County — Master Gardener

Schiavone, F. (2017.) File:Ants with rock.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

USDA. (n.d.) Unusual Animal Pollinators

US Forest Service. (n.d.) Moth Pollination

Xerces Society. (2014.) Help Your Community Create an Effective Mosquito Management Plan