Written by: Reva Grewal

Food. Sustenance. Nutrition. A crucial part of our daily lives that every living organism on this planet requires to survive. It is well-known and well-documented that many countries across the world have citizens who do not get proper access to the nutrition that they require to survive (United Nations, n.d). Canada is considered a G7 country (Global Affairs Canada, 2021), and for those who are fortunate such as me, I do not have to think twice about whether I will be able to see food on the metaphorical dining table. However, despite Canada’s economic status, Indigenous communities are still struggling with food insecurity at disproportionate rates in comparison to their non-Indigenous counterparts (Skinner et al, 2013). This article will detail what food insecurity means in the context of this article, the statistics (data), causes for this issue, and what can be done to help. This article has been written with the purpose to bring awareness to this ongoing issue. The term “Indigenous” is used to describe three groups: First Nations (FN), Metis, and Inuit. The focus of this article will be on the First Nations population, as it comprises 60% of the Indigenous population in Canada (Skinner et al, 2013).

Food insecurity and how it is defined in this blog post can be defined by using the University of Toronto’s definition: “Household food insecurity is the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints” (University of Toronto, n.d). Other constraints can exist, such as time (University of Toronto, n.d).

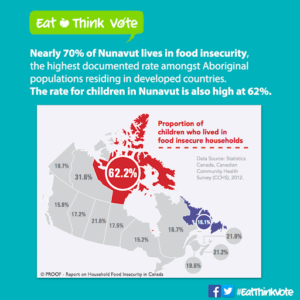

Over ⅓ of Indigenous peoples live on-reserve (University of Toronto, n.d), and the experiences of both on-reserve and off-reserve Indigenous peoples will be examined. The numbers are startlingly high. “Indigenous people living off-reserve are also more than twice as likely to experience hunger and food insecurity compared with non-Indigenous Canadians; 27% of Indigenous Canadians are food insecure compared with 11% of non-Indigenous households (30)” (Chantelle et al, 2020). The data utilized for this post comes from First Nations peoples residing both on-reserve and off-reserve in Ontario (Chantelle et al, 2020). For First Nations people that reside on-reserve 54.2% are food insecure and for the Inuit food insecurity ranges from 45-69% depending on the location. For those off-reserve, 24% experienced a compromised diet and 33% experienced food insecurity (Skinner et al, 2013). The data varies from study to study but all of the data points to the same conclusion: Indigenous communities in Canada disproportionately experience food insecurity compared to those who are non-Indigenous.

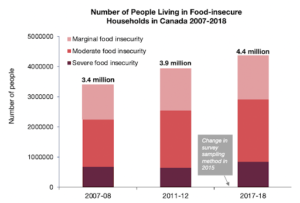

A graph showcasing food insecurity rates in Canada (Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2007-08, 2011-12, 2017-18)

So what are some of the causes of this issue (food insecurity and inadequate nutrition)? This question is very nuanced and complex, however, I will summarize a key few reasons that various studies (linked below) have suggested. One of the reasons for inadequate nutrition in particular is the rapid urbanization that has been occurring in Southern Ontario. Access to traditional foods has been declining and diet diversity has been decreasing. This has led populations in Southern Ontario to consume an increasing amount of fats, sugar, salts, and processed foods which has negative health consequences for everyone in Southern Ontario; disproportionately affecting First Nations communities (Chantelle et al, 2020). According to Canadian Feed the Children: “Indigenous communities in Canada have faced significant and ongoing challenges since European settlers arrived and established colonies on Indigenous territories. The loss of land rights, outlawing of Indigenous practices and languages, and discrimination towards Indigenous people have perpetuated a food insecurity crisis with serious implications for health and well-being” (Canadian Feed The Children, 2019). This website will be linked below and is a good resource for further information, which I implore you to read about.

Furthermore, Residential schools have had lasting impacts on Indigenous communities all across Canada (Wilk et al, 2017). Those who were subject to such horrid treatment often had parts of their culture erased, such as knowledge of preparation of traditional foods (such as cutting meat or working with fish) and the loss of land has significantly hindered traditional hunting and fishing practices (Canadian Feed The Children, 2019). Continuing, poverty is a significant barrier to obtaining proper access to adequate nutrition. “Indigenous households in Canada are more likely than non-Indigneous households to experience the sociodemographic risk factors associated with household food insecurity (e.g. extreme poverty, single-motherhood, living in a rental accommodation, and reliance on social assistance)” (University of Toronto, n.d). Even taking the factor of an increased vulnerability to sociodemographic factors into account, the risk for food insecurity remains high.

Another reason for this is climate change (which you can learn more about by traversing the other blog posts on this page) and pollution. These factors affect the food that is available to community members who choose to obtain their nutrition through more natural sources, as it limits foods that can be found in nature. Lastly, some Indigenous communities reside in remote areas (such as Northern Canada) where market food (food found in grocery stores) is more expensive due to higher shipping costs (Food Secure Canada, 2016). Also, there is an added issue with government policy and program coordination in Northern Canada, with that discrepancy leading to issues for the market food supply. Many other reasons can be described as this is a problem at the systemic and socioeconomic level, however, I will move to provide ways that we as individuals can help (University of Toronto, n.d).

Food Insecurity in Northern Canada (Food Secure Canada, 2015)

35% of Inuit households struggle with food insecurity (Source: HuffingtonPost.ca) (Inzinga, 2016)

There are a couple of things that we can do as individuals. The organization “Canadian Feed the Children” supports the right to food security for First Nations children in Canada. Donating on their website (which will be linked below) leads to nutrition education, school nutrition programs, and community mobilization occurring to help the First Nations community (Canadian Feed The Children, 2019). Various organizations working towards ending poverty and food insecurity amongst Indigenous organizations can be supported. Seeing as we are not a governmental entity, it is difficult to control policy. However, certain organizations do food security policy work such as Food Secure Canada. True North Aid provides support for Indigenous communities living in Northern Canada where your time or money can be volunteered. Furthermore, it is important to support organizations that conduct research on food insecurity in Indigenous communities. This data helps to keep us informed as to the status of this issue, and can help to inform decisions and movements in regards to resolving this issue (Imperial Business Insights, 2019).

Setting up local gardens is a good way to combat food insecurity, so supporting Waterloo School Regional Food Gardens is a great way to help out! School gardens promote a sense of community amongst participants. Furthermore, they provide lifelong skills and tools to be able to cultivate and grow plants. These fruits and veggies that are grown support good nutrition (Canadian Feed The Children, 2019). Community gardens function similarly, utilizing a broad audience. They offer nutritious foods almost year-round (Adam, 2011). The organizations I provided best address food insecurity, and there are other organizations I will link below that address some causes of food insecurity, such as housing and poverty*. In general, supporting Indigenous artists, creators, businesses, organizations, and charities is a great way to uplift communities (Deer, 2019).

To conclude, food insecurity disproportionately affects Indigenous communities in Canada. This is due to a multitude of reasons such as generational trauma and residential schools. As individuals, we can support organizations that work to achieve food security for Indigenous communities.

*Waterloo Regional School Food Gardens is not in affiliation with any of the organizations that have been listed in this article.

Organizations to support:

The Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Fund https://downiewenjack.ca/

Canadian Feed the Children: https://canadianfeedthechildren.ca/ways-to-help/fundraising-campaigns/first-nations-nutrition/#how-helps.

True North Aid: https://truenorthaid.ca/volunteer/

The Indian Residential School Survivor Society: https://www.irsss.ca/donate

The Native Canadian Center of Toronto: https://ncct.on.ca/

Food Secure Canada: https://foodsecurecanada.org/

A more comprehensive list can be found here: https://ottawa.ctvnews.ca/indigenous-charities-in-ottawa-to-support-this-canada-day-and-beyond-1.5491420

Works Cited:

Adam, K. L. (2011, January). Community Gardening. National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service. https://attra.ncat.org/product/Community-Gardening/.

Canadian Feed The Children. (2019, December 23). First Nations Nutrition Program – First Nations Hunger. https://canadianfeedthechildren.ca/ways-to-help/fundraising-campaigns/first-nations-nutrition/#how-helps.

Canadian Feed The Children. (2019, October 9). Sprouting seeds of knowledge: Classroom gardens improve food security. https://canadianfeedthechildren.ca/the-feed/sprouting-seeds-knowledge/.

Chantelle Richmond, Marylynn Steckley, Hannah Neufeld, Rachel Bezner Kerr, Kathi Wilson, Brian Dokis, First Nations Food Environments: Exploring the Role of Place, Income, and Social Connection, Current Developments in Nutrition, Volume 4, Issue 8, August 2020, nzaa108, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa108

Deer, K. (2019, December 7). Where to find your beaded bling and gifts with a cause | CBC News. CBCnews. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-holiday-gift-guide-1.5387431.

Food Secure Canada. (2016, April 26). Affordable food in the north. https://foodsecurecanada.org/resources-news/news-media/we-want-affordable-food-north

Food Secure Canada. (2015, November 11). Hunger still thriving in Canada, particularly the North. https://foodsecurecanada.org/resources-news/news-media/hunger-still-thriving-canada-particularly-north-0.

Global Affairs Canada. (2021, June 13). Canada and the G7. GAC. https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/g7/index.aspx?lang=eng.

Imperial Business Insights. (2019, September 23). How Data Science Will Help Solve Many Of The World’s Most Pressing Challenges. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/imperialinsights/2019/09/23/data-science-for-social-good/?sh=68b32c25464b.

Inzinga, M. (2016, October 25). Indigenous food insecurity. The Xaverian Weekly. https://www.xaverian.ca/articles/2016/10/25/food-insecurity-in-indigenous-communities.

Skinner, K., Hanning, R.M., Desjardins, E. et al. Giving voice to food insecurity in a remote indigenous community in subarctic Ontario, Canada: traditional ways, ways to cope, ways forward. BMC Public Health 13, 427 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-427

United Nations. (n.d.). Food. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/food#:~:text=Current%20estimates%20are%20that%20nearly,are%20still%20found%20in%20Asia.

University of Toronto. (n.d.). Household Food Insecurity in Canada. PROOF. https://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/.

Why is there food insecurity in Canada? Canadian Feed The Children. (2021, March 8). https://canadianfeedthechildren.ca/the-feed/why-food-insecurity/.

Wilk, P., Maltby, A. & Cooke, M. Residential schools and the effects on Indigenous health and well-being in Canada—a scoping review. Public Health Rev 38, 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0055-6