Written By: Emily L

Edited by: Sarah

Designed by: Nabiha

Published by: Maryam Khan

Ash Genus

Ash trees. If you are, for some reason, still unsure about what this blog will be ranting on, t’is ash trees. The curious plants that are strangely named similarly to their burnt remains.

To clarify one thing, ash is not a species; it is a genus which means it is one step higher on the hierarchy of classification. The scientific name for this genus is Fraxinus, and it belongs under the Oleaceae family, commonly known as the olive family. Examples of species under the ash genus would be:

- White Ash

- Black Ash

- Blue Ash

- Chinese Ash

- European Ash

Seeing a connection yet?

The genus contains between 45-65 different species of trees and shrubs, many of which are spread across the northern hemisphere, while certain ones also extend through the tropical forests in Mexico and Java.

Aside from the larger timber trees that can grow 18-34 metres, overall, the trees in the ash genus are small to medium in height. The large majority of ash trees are deciduous, their branching is opposite, and they have odd numbered, pinnately compound leaves. Their leaflets are finely toothed and usually range from 5 to 11 per vein; the specific number depends on the species and variety. For each vein the leaflets should all be approximately uniform in size, excluding the bottom-most two (basal leaves) which will be slightly smaller.

Most ash species have rather low-key, small flowers that grow in clusters. The flowering ash(Fraxinus Ornus), though, grows fragrant, eye-catching ivory flowers. The seeds of ash trees, called samsaras, are single-winged and droop downwards. They look somewhat similar to half of a maple seed, and the samsaras will turn from green to brown as the summer passes.

As for general branch shapes, larger branches tend to grow longer while the comparatively smaller branches, known as twigs, grow stoutly. Ash branches have the habit of growing upwards, and the ends of the twigs will usually form a sort of three-pronged trident shape out of buds. The buds are typically shorter and blunter. I do have to say that each individual ash species makes its own alterations on the cookie cutter, “default” ash tree, so don’t expect every species to follow this exactly.

Ash trees are hardwood producers; the white ash(Fraxinus Americana) and green/red ash(Fraxinus Pennsylvanica) are well loved timber trees for their, well, timber. Their wood is said to be strong, resilient, and stiff, yet light. It is used in the manufacturing of many different sports sticks/bats/rackets, paddles, oars, and agricultural tools. The black ash(Fraxinus Nigra), the blue ash(Fraxinus Quadrangulata), and the Oregon ash (Fraxinus Latifolia) each also have valuable wood used in barrel-making, furniture making, and interior panelling.

The Chinese ash(Fraxinus Chinensis) collects the byproduct of an insect that can be processed into Chinese white wax. It is mainly used to make candles, polishes, and paper sizing, but it has also been utilized in traditional medicines to treat certain ailments.

Ash trees are generally a popular choice when it comes to making urban spaces greener as they grow quickly and are more resistant to urban living conditions. The natural foliage increases property value, air quality and lowers the cost of heating/AC. They also provide a bed for wildlife.

The Mexican ash(Fraxinus uhdei), for example, is widely planted along the streets of Mexico City, while the flowering ash can be commonly found in southern Europe. The European ash(Fraxinus Excelsior) is, as its name may hint, also extensively planted in Europe. This species’s varieties have been cultivated for centuries in landscaping; its most distinguished varieties are those with dwarf-like or weeping habits(either grow smaller or the branches droop like a willow tree), warty branches, and variegated and curled leaves. The European ash and the Manchurian ash(Fraxinus Mandshurica) are the two most common non-native ash trees in Canada that have been purposefully planted outside their normal range. Some yet to be mentioned non-native trees regularly planted in Canada are the narrow-leafed ash(Fraxinus Angustifolia) and Bunge’s Ash(Fraxinus Bungeana).

But that’s only talking about the trees that were later introduced. Canada has 5 native ash species: green/red(F. Pennsylvanica), black(F. Nigra), white(F. Americana), blue(F. Quadrangulata), and pumpkin ash(Fraxinus Profunda). Ash trees tend to be planted in the southern central to eastern parts of Canada. Seeing as they are deciduous, though, is that really any news?

There is, for any readers who have heard of it and are confused, the mountain ash. Mountain ashes(Sorbus) are not part of the ash genus; they are a completely separate genus of their own, comprising 100 or so different species, 4 of which are native to both eastern and western Canada. They aren’t very closely related either, for the mountain ash genus belongs under the rose family(Rosaceae).

Back to the topic of Canadian ash trees. Fraxinus Pennsylvanica is commonly known as green ash in the US, but was called red ash in Canada. Confusingly, this species has 2 varieties found in Canada: the northern red ash(F. Pennsylvanica var. Austini) and the green ash(F. Pennsylvanica var. Subintergerrima). In the more recent years, the name green ash is more often used in relation to the emerald ash borer, a pest now frequently associated with the ash trees. The blue ash and pumpkin ash are both few and far between; the latter only found in specific locations of southeastern Ontario near Lake Erie. The former has very striking four-faceted twigs similar to square prisms.

More information about identifying ash trees in Canada can be found in this detailed survey manual.

Ash trees are vulnerable to yellowing leaves, anthracnose, and rust. Anthracnose is a blanket term for a group of related fungal diseases that cause dark lesions, and in severe cases, sunken lesions, cankers on twigs and stems. It is also known as leaf, shoot, or twig blight. Tree rust is another type of fungal infection that causes discoloured spots on the underside of leaves that gradually darken in colour. As it worsens, the spots will turn into bumps on affected leaves and leaves will eventually wither and fall.

A third fungus-caused disease that reaped the lives of many ashes in Europe is the chalara ash dieback disease. This tree sickness originates from the Hymenoscyphus Fraxineus fungus, and it causes leaves to wither and, wouldn’t you know it, crown dieback.

Now, the final threat that ash trees face is the previously mentioned emerald ash borer. This threat only appeared in the early 2000s yet has grown so large in North America that the name of ash trees basically always drags along mention of the EABs as well. Buy one get one free. That leads us into section two of this blog.

Emerald Ash Borers

Emerald ash borer beetles(Agrilus Planipennis) are an invasive insect species that swiftly kills native and non-native North American ash trees. This insect originates from Asia, where it wasn’t nearly as detrimental to the trees there; it was only able to claim already sick and dying trees. 2002 was when it was first discovered in North America, in the Detroit, Michigan vicinity. It is theorized that the beetle was unknowingly smuggled in by way of infested ash wood products, and tree ring analysis suggests that they had already made their way here as of the early 1990s.

The bug is a species of wood boring beetle; its shimmery metallic green exoskeleton earning its name.

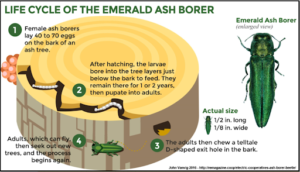

Like other insects, it starts as an egg. EAB eggs are usually laid between the crevices of or underneath the ash’s bark. It takes 1-2 weeks of incubation before the disc-shaped eggs hatch, after which they burrow directly under the egg and straight through the bark until they reach the cusp between bark and wood. The larvae continue to make winding tunnels into the wood; after 4 moults, they chew a chamber where they double back on themselves, forming a squished J shape. This is the prepupae stage, wherein they shall hibernate through the winter. Around 20% of those in southern Ontario and a significantly higher proportion of those further north are unable to mature in the first winter and thus must go through a second before gaining the ability to advance to the pupa stage. Then around late May to early June, the centimetre long adult beetles burrow out of the tree in full glory, forming a D-shaped exit hole characteristic to the species. The adults dine on ash leaves for up to 2 weeks, mate, and the cycle repeats.

The fully grown beetles, only munching on some leaves, do not do nearly the same amount of damage to host trees when compared to their destructive spawn. The worms, by tunnelling here and there and turning the tree to swiss cheese, inadvertently kill the tree by girdling the trunk. Girdling is a method that kills parts of or the entire tree by stripping a ring of bark or constricting its circumference. It essentially deprives a tree of nutrients, similar to how a tight rubber band can stop blood flow to a limb, thus killing it. The wood and bark is so completely riddled with holes that it can no longer transport water and nutrients to the rest of the tree.

Signs that there may be an EAB infestation in a host tree would include crown dieback, bark deformities, a plethora of D-shaped emergence holes and woodpecker feeding holes, as well as shoots and plants growing out of the trunk, roots or branches. However, these signs only show up when the population has already grown large.

Signs that there may be an EAB infestation in a host tree would include crown dieback, bark deformities, a plethora of D-shaped emergence holes and woodpecker feeding holes, as well as shoots and plants growing out of the trunk, roots or branches. However, these signs only show up when the population has already grown large.

Currently, there are no native predators that can fully contain the insect. Woodpeckers are the only ones that even feed extensively on them. Emerald ash borers can spread locally through flight, they can hitchhike on travelling vehicles, and the larvae may hide in infested wood. It has been observed that the beetles can usually survive down to -30℃, and their habitat beneath the bark is even warmer than outside temperatures; this suggests that the beetles can survive every natural habitat of ash trees. 99% of the ash population of an area is doomed to die within 8-10 years the moment the first borer comes strutting in.

Besides the blue ash, which has a very slight resistance to the insect, all native Canadian ashes are highly susceptible and heavily hit by the emerald ash borer.

The overwhelming amount of ash tree deaths will evidently affect local ecosystems. This genus is vital to streamside environments. A lack of ash trees in streamside habitats will lead to soil erosion, gaps in the canopy, a rise in water temperatures due to increased solar exposure, and reduced biodiversity of ash dependent species which will open up gaps for invasive species to barge in. Forest species compositions will undoubtedly change, therefore evoking a shift in natural forest succession and nutrient cycling.

In the cities, everything positive that the trees contribute will inevitably be impacted once they die; not only that, the municipal government even loses money as they have to now remove the murdered trees as well.

So, what has been and is being done to minimize these already occurring damages? Well, there have been a lot of scientific tests and studies conducted to figure out a way to halt these bugs’ conquest. Scientists have been sampling trees, developing monitoring tools(the pheromone trap), and testing out potential ideas. A current idea is the introduction of a predator that will hopefully keep the population numbers under control. Fungal pathogens, for example, have been recovered from the ash borers, and scientists are trying to see whether they can be exploited to further affect the pests. Some recent tests here in Canada are suggesting that perhaps inviting over parasites that originally heavily controlled the EABs’ numbers back in Asia will be a solution to this issue. In fact, the US has already imported, cultured and released three parasitoids native to China that fit this bill. In Canada only one of the three has been released to a single site only in Ontario.

Links:

Britannica

Image sources, from top to bottom

1 https://horttrades.com/urban-tolerant-trees-know-them-and-grow-them

https://eabguelph.wordpress.com/2013/06/28/ash-tree-leaves/

2 https://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/trees/plants/white_ash.html

https://www.treeguideuk.co.uk/common-ash-tree-identification/

https://inaturalist.ca/guide_taxa/473051

4 https://arboretum.uoguelph.ca/thingstosee/trees/blueash https://pnwhandbooks.org/plantdisease/host-disease/ash-fraxinus-spp-anthracnose

https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/115907/researchers-test-solution-fungal-disease-trees/

http://www.invadingspecies.com/invaders/forest/emerald-ash-borer/

6 https://modernfarmer.com/2021/09/emerald-ash-borer-ash-timber-industry/

http://www.emeraldashborer.info/