Written by: Declan Murphy

Edited by: Rayna Almas

Designed by: Kiya Tavascia

Published by: Rayna Almas

As we approach Remembrance Day, we recall the sacrifices of people who have served and died for our country. Today, we will also take a look at how the ways those soldiers ate still impacts our foodways.

They say an army marches on their stomach, and it’s true. In any war, logistics and supply chains are critical to success or failure, and the World Wars were absolutely no exception. Research done by military experts on innovations in cooking, transportation and preservation of food have impacted diets around the world. If you have eaten something frozen, dried or microwaved recently, you have felt the effects of the World Wars in your own kitchen.

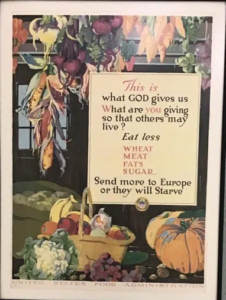

Amongst the families left behind, rationing, gardening and canning on the homefront became iconic of the wartime eras. Wives and mothers drew on traditional food knowledge and innovated new ways to stretch and extend supplies and allow countries to survive the war. Their resilience and ingenuity added to our collective understanding of home economics. Further, the way agriculture and food manufacturing responded to the war effort has made a lasting mark. The movement away from sugar, wheat and meat on the homefront during the wars are partially responsible for the dramatic increase in the North American reliance on corn, including corn starch and corn syrup, for example. When animal lard was needed overseas, Crisco developed vegetable shortening, which is still common today.

In terms of military research and development, many 20th century food innovations started out as ways to feed the troops and were then normalized at home. The wars moved militaries away from the older food preservation methods of salting, drying and smoking, and away from glass jars. Modern grocery stories are filled with dehydrated, instant, concentrated, vacuum packed, freeze dried, simulated, shelf stable, reconstituted, canned, processed and frozen foods today because of these two wars.

By the end of World War I (1914-1918), there were approximately 75 million active soldiers, and governments had to figure out how to feed them all regularly. Each soldier required about 3 to 4 thousand calories a day, depending on their duties. Most of them were in the thick of fighting, dug out in trenches, or on boats, and many were on the move. What a logistical challenge! As much research was going into food technology as there was weapons. By necessity, the war effort steadily moved away from fresh foods and focused on processed food, since they could travel without spoiling.

Semi-mobile field kitchens were used to feed people near the rear, but portable tinned rations were an essential part of the solution. Nothing else worked quite so well in the trenches as simply equipping soldiers with can openers and stocking the storage with canned milk, soup, stew, meat, vegetables, fruit and beans. Small portable stoves for heating food in tins became necessary tools on the front, though canned foods could also be eaten cold in a pinch.

Tinning wasn’t really a new technology. First developed in the 1700s, industrial canning in glass became somewhat normal by the late 1800s, when metal cans were first produced. However, WWI increased the demand for tinned food in such a large quantity and variety that the canning industry blossomed. This triggered a sharp increase in the consumption of canned food outside the military. After the war, canning companies had to find new, domestic markets during peacetime, and they became a standard “modern convenience” in the American and Canadian home.

Similarly, a variety of dried and ersatz products were developed for field kitchens and then introduced into domestic kitchens, including powdered eggs, simulated drink mixes and broth cubes or concentrates. Instant coffee wasn’t specifically invented for soldiers in WWI, but it was significantly improved upon for the guys in the trenches and would soon become common in households, as well. This switch was a sign of things to come in the next war.

During the Second World War (1939-1945), tinned rations continued to be important. Spam, the well known canned meat found in grocery stores around the world today, was invented for WWI and then sold to families as a pantry staple for generations afterwards.

But technology had advanced beyond cans and simple dehydration since the Great War. Food processes like concentrated fruit juices, dried/reconstituted foods, new freeze drying techniques and vacuum packaging were developed during WWII. These new methods made international shipping easier and cheaper by increasing the volume of calories transported while also cutting down the weight of materials. Dried yeast and packaged cake mixes were born from this food research in order to improve field kitchen yields. In the foxholes, hot meals could be had through “boil in the bag” ration packs. Tubes of processed shelf stable peanut butter and jam were tasty, long-lasting and rich in calories, fat and salt. Dehydrated meats, instant oatmeal and powdered milk and cheese were lighter and required only water to rehydrate and consume on the go. The process for dehydrating cheese powder made Kraft Dinner a reality, and, in 1948, the Frito company would apply it to extruded corn puffs to produce Cheetos, a common favourite today. Meltproof candy was also invented for soldiers, so they could carry treats in their pockets. The most famous example of these was M&Ms!

Even more impressive, the American forces worked to provide ice cream in order to boost morale. Hospital ships, in particular, were well stocked with ice cream for convalescing soldiers. Freezer technology was improved by leaps and bounds during WWII to allow for more flexibility in logistics, and Navy ships were equipped with the best available technology. Making use of these innovations, the American Air Force developed individual portion pre-cooked frozen meals served in disposable, heatable compartmentalized trays for crews and personnel being moved in large numbers. In 1953, Swanson would turn this into frozen TV Dinners, an iconic “modern meal” found in many homes throughout the following decades. (This trend would also encourage the development of microwave ovens in the 1940s, though they wouldn’t become popular in American home kitchens until the 1970s.)

For better or for worse, when the wars were over all of these innovations were repackaged for sale to homes across the continent and the world, and families also moved away from fresh, salted and smoked foods.

The wars had caused a massive boom in food processing and packaging businesses, and these companies adapted to peacetime in order to survive. Processed food companies were able to sell the American consumer on the idea that freeze dried, vacuum sealed and frozen foods were the future, and more labour intensive traditional foods “from scratch” were no longer modern enough for upwardly mobile families. Later, as globalization of manufacturing and trade expanded, the technologies innovated for the trenches became central to doing international business. Companies like Coca-Cola, Nestle and Campbell’s used the processes they had developed to supply the troops to supplant homemade and locally made foods in many homes around the world.

So, next time you eat something made a thousand miles away, remember the history and development it represents. WWI and WWII were not just events of the past that took place far away from here. Our foodways are still impacted by the World Wars, and will never be the same again.

Sources:

Anon. (2024.) World War I and Food – Museum of the American G.I. Museum of the American G.I. https://americangimuseum.org/world-war-i-and-food/.

Canadian War Museum. (2019). The War Economy – Farming and Food | Canada and the First World War. Canada and the First World War. https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-home-during-the-war/the-war-economy/farming-and-food/.

Christopher, C. (2023.) How WWI changed how and what Americans eat at mealtimes. The Doughboy Foundation. https://doughboy.org/how-wwi-changed-how-and-what-americans-eat-at-mealtimes/.

Cronier, E. (2021.) Food and Nutrition / 1.0 / handbook. 1914-1918-Online (WW1) Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/food-and-nutrition/.

Dudley, M. (2024.) Food on the Frontlines. National Museum of the Pacific War. https://www.pacificwarmuseum.org/learn/articles/food-on-the-frontlines.

Eberle, U. (2024.) From the Front Line to the Freezer Aisle. Science History Institute. https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/from-the-front-line-to-the-freezer-aisle/

Imperial War Museums. (2018). Rationing and Food Shortages During the First World War. Imperial War Museums. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/rationing-and-food-shortages-during-the-first-world-war.

Imperial War Museum. (2018). The Food That Fuelled The Front. Imperial War Museums. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-food-that-fuelled-the-front.

Koehler, J. (2017.) In WWI Trenches, Instant Coffee Gave Troops A Much-Needed Boost. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/04/06/522071853/in-wwi-trenches-instant-coffee-gave-troops-a-much-needed-boost.

National Army Museum. (2024). An army marches on its stomach | National Army Museum. Www.nam.ac.uk. https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/army-marches-its-stomach.

National Parks Service. (2023.) Post World War II Food. U.S. National Park Service. Www.nps.gov. https://www.nps.gov/articles/post-wwii-food.htm

Sarkar, P. (2025.) How World War II Changed Everything About Packaged Food. Medium. https://blog.probirsarkar.com/how-world-war-ii-changed-everything-about-packaged-food-1eea8df416ed.

Wassberg Johnson, S. (2024.) Category: World War II. The Food Historian. https://www.thefoodhistorian.com/blog/category/world-war-ii.

Whirlpool. (2023.) History of the microwave oven. Whirlpool.com. https://www.whirlpool.com/blog/kitchen/history-of-microwave.html.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025.) Canning. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canning.

Wikipedia contributors. (2021.) Spam (food). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spam_(food).