Written by Declan Murphy

Edited by Kiritika Rana

Designed by Ayesha

Published by Kiritika Rana

Seed harvesting is a time-honoured tradition that has sustained human agriculture for generations, and you should learn how!

Plants produce seeds. For wild plants, their seeds are left up to the fates and are sewn by chance through the plant’s natural dispersal mechanisms. For thousands of years of human agriculture, however, seeds have been carefully harvested or collected, saved, and used to propagate new plants in the subsequent growing seasons. This is the basic idea of seed saving, and gardeners and farmers around the world are still doing it, despite the existence of industrial seed sellers that seek to control the ownership and use of seed.

In brief, seeds are produced by a plant after their flowers have been pollinated and their flower (or fruit or berry or pod) has ripened. Different plants will be ready in different ways and after different periods, or at different stages. Tomato seeds, for example, come from the ripened tomato fruit, while lettuce seed comes from a lettuce flower, which only blooms long after the lettuce could have been picked for eating. In many cases, you must make the decision to forgo eating a plant to allow it to go to seed, but for many plants, you can have your seeds and eat the plant, too!

Many plants produce seeds every year, while some only seed every second year or so. If you harvest the seeds before they are ripe, they won’t produce anything but disappointment, so it’s worth taking the time to learn. It takes a certain amount of “seed knowledge” to seed harvest.

You should look up the individual plants you wish to grow into seed, to make sure you know how and when to harvest the seeds. You will learn how to observe your garden with practice. It may take you a few tries to get things right, and that’s okay. Keep trying!

Seeds can be harvested from nearly every plant. Some seed savers collect seeds from any and every plant, but most experienced seed savers select seeds from specific plants that have something special about them – perhaps a higher yield or a better fruit. That was the first form of selective breeding humans probably did with their crops. Collecting seeds from healthy, successful seeds will ensure that the next generation will be well suited to the same garden plot in subsequent years.

It is also possible to collect seeds from wild plants, but that’s a bit trickier. Please, don’t select just any plant that is pretty! You need to identify the species and make sure it is not an invasive plant, first, to avoid propagating something that could harm your ecosystem. Only collect wild native plant seeds in places where the plant is abundant because you don’t want to interfere with the plant’s reproduction in its location. Further, if it’s a rare or endangered plant, or a plant growing on a nature preserve, you should not interfere with the seeds without permission.

Exactly how to harvest seeds will depend on the plant, but it is typically a process of picking the seeds from a plant at the right time and cleaning and drying the seeds thoroughly so they will be stored without mildewing.

You should harvest the seeds only when they are ripe, and only on a warm, dry day. Some seeds can be easily harvested by hand, but some will require clean scissors or pruners, and you should be ready with paper bags to catch your seeds or fruits in. “Dry seeded” plants are those which produce seeds from a dried out, faded flower, and those are probably the easiest, with the fewest steps. “Wet seeded” plants, however, involve scooping the seeds out of a fruit, like a fully ripened cucumber or pepper, which may require some extra attention to cleaning and drying.

Cleaning seeds not only reduces the bulk but also protects your seed collection from hitchhikers, like mould spores and insect eggs. Seeds are cleaned by being removed from the non-seed debris, either the fruit that encases them or the petals/leaves and pods around them. For seeds coming from flowers, this is sometimes easier to do after the seed is dry because you can sometimes simply blow away the debris through winnowing, or by sifting.

To dry the seeds, you will need to spread them out in a dry, warm place, out of the sun. Smaller seeds will dry fairly quickly, but larger seeds, like beans, will take longer. You can place the seeds on plates or trays in a single layer, and stir or turn them daily until they are hard and dry. They will need proper airflow, and you’ll want to avoid letting them stick to each other and surfaces.

You should be careful throughout this process that you have a system in place to recall which seed is which! When it comes time to store the seed, you will need to carefully label the seed with the species/variety, location and date.

Once the seeds are cleaned, dried, and labelled, they can be stored for future use. Remember, your seeds are still sort of alive, they are just dormant. You don’t want them wet, but you don’t want them to completely desiccate, either. You will still want to avoid mildew, so keep them from sweating and maintain some airflow. A low humidity level is best, at about 5-10%. Some people use silica pouches to maintain optimal humidity, though a nice, low-tech way to prevent mildewing is to keep them in envelopes. A nice, cool, stable temperature is best, as well, though they can handle some temperature changes, and you will want to keep them away from direct sunlight. You will also want to keep your seeds safe from any animals or insects that will view them as a very tasty winter snack!

If you harvest, clean, dry and store your seeds correctly, you should have ample resources to start your garden anew the next season, and perhaps the next season or two depending on the longevity of the species’ seed.

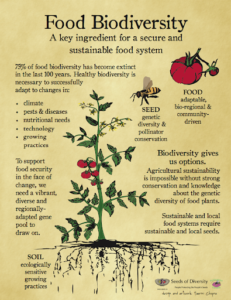

Seed saving is one of the most important things a gardener can do to resist the takeover of agriculture by the handful of companies that seek to control the world’s food seeds. Having the ability to save and share seeds increases food sovereignty by placing the power to grow food into the hands of people, not corporations. It also preserves biodiversity and rejects the monoculture of commercial farming that offers only a very limited choice of seed to gardeners and farmers. It preserves small-scale local varieties, and, thus, keeps the species strong for future generations.

Seeds are a part of our human heritage, and it’s important to maintain this tradition.

Heirloom seeds are those which have been cultivated and saved for generations in a location. By selecting the best plants from our garden for seed harvesting, we can perpetuate plants that will continue to thrive in our specific location, saving the gardener or farmer money by allowing them to avoid paying out for new seeds every year. With luck and attention to detail, the gardener or farmer can also continue to strengthen their plants by picking the best plants and seeds year after year, creating stronger, healthier, and more productive plants with each generation.

The Canadian organization Seeds of Diversity continues to work to preserve the tradition of seed saving. For more information, please check out the resources offered by Seeds of Diversity to start your seed bank!

Sources

Anon. (n.d.) Image: Orange corn seeds. PxFuel.

Adrees, A. (2018.) File:Harvesting crops of wheat.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

Gibson, A. (2020.) Seed Saving Part 1: The Lost Art of Seed Saving | Garden Culture Magazine

Gibson, A. (2020.) Seed Saving Part 3: Harvesting & Processing Seeds | Garden Culture Magazine

Gibson, A. (2020.) Seed Saving Part 4: Storing And Testing | Garden Culture Magazine

Hughes, M. (2022.) How to Save Seeds from Your Garden to Plant Next Year

Makeev, D. (2012.) File:Seeds – sunflower and cucurbita seeds. img 02.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

RHS. (n.d.) Seed: collecting and storing / RHS Gardening

RBG Kew. (n.d.) How to save seeds | Grow Wild | Kew

Rubin, D. (2021.) Seed Saving Basics with Dan Rubin

Seeds of Diversity. (2023.) Seeds of Diversity

Weich, S. (2021.) How to collect and plant native wildflower seeds – Farm and Dairy